By Tracy Burkhard

I used to chase birds in the Bayou – I’d chase them in water and in mud and through the reeds. Of course, this wasn’t merely a hobby. Rather, I was in the midst of an exciting field season: I was one of a team of four sent to Port Sulphur, Louisiana to study the effects of the 2010 BP oil spill on marsh communities. I wrote the following essay during this field season to capture my life working with seaside sparrows, a small songbird that inhabits the coastal marshes of the Southeast United States.

May, 2013

If you search for Port Sulphur on a map, you will note that it is located almost exactly halfway down a narrow strip of land into a vast expanse of water. Thirty minutes’ driving southeast will take you to The End of the World—Venice, Louisiana—where the road ends abruptly at the edge of the ocean, and you can go no further in your car. A two minutes’ walk east from my house directs you over the levee to the Mississippi; the Gulf of Mexico laps into the opposite bank.

My Louisiana is flat, humid, and dirty. The murky waters vomit back up the forgotten muck of the land, spewing chunks of styrofoam, withered tires, and weathered plastic sacks amongst the old fish carcasses and shells littering the levee. Considering these sporadic floods, none of the buildings in town are built with any sense of permanence. Rather, they are built to survive—that is, to be transportable. Homes are nothing more than small portable boxes resting on concrete blocks, elevated from the tide, waiting to be whisked away. Even the Subway (one of two restaurants in Port Sulphur) and the town library (WE NOW HAVE INTERNET! announces a door sign) are small portable boxes set on platforms.

A typical day in the life is as follows:

5h00: Groggily, we shut off alarms and crawl to the kitchen. We sleepily chase our breakfasts with sips of coffee or tea.

6h00: We’ve packed up our red truck and small white motorboat with the equipment we will need for the day: boxes of bird and mammal gear, an ice chest, life jackets, various collection vials, our GPS. We leave the house and drive three miles north to our boat launch, a small canal called Happy Jack.

6h20: We have dubbed our boat the Brazen Sparrow (we so christened her with a box of white zinfandel the other night), and she seats the four of us and all our equipment comfortably. Fishermen and their families live in wooden stilt houses bordering the waterway, so when we launch, we putter quietly past these sleeping homes

6h35: We exit the housing zone, and we slowly accelerate, launching our boat into plane. The cool wind lashes our faces, and hunching forward, we sandwich cold hands between our knees. We speed through a maze of canals connecting us to the Gulf of Mexico. We weave through clusters of pylons and past stationary oil rigs, waving to anchored fishing boats. It’s a breathless, fast journey across the ocean, and our boat slashes mercilessly at the dark waves, which bleed a foamy white wake. Forster’s terns flit through the sky and gracefully plummet into the water, emerging triumphantly with fish in bill. Sleek black cormorants perch upon PVC poles, breasts to the sun, shaking out wings heavy with water. Slate-colored dolphin fins undulate through the surface, sometimes venturing close to our boat when we lure them in by rapping our knuckles on the sides of the boat.

7h00-14h00: We arrive at one of our study sites. Our sites are scattered amidst the salt marshes of several bays lining the Gulf. The marshes are flat golden expanses composed of rushes and sedges that thrive on the salted, spongy mud. The sound of metallic calls throughout the site announces the presence of seaside sparrows, though the small brown birds themselves are nearly invisible in thick clumps of vegetation.

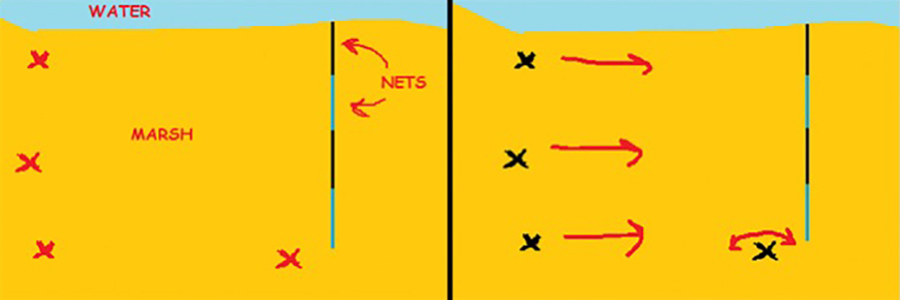

Catching birds is one of our main daily tasks. We catch the sparrows to band them (the method to identify birds by putting a unique combination of colored plastic bands and a metal band with a unique number on their legs) and to take a small blood sample from them (to obtain samples for DNA testing and hormone assays). To do this, we use a technique called mist netting. We string four nets (2m high, 10m long) of fine nylon threads taut between tall poles that we sink in the soft soil. We set them in a line, starting from the water’s edge and running perpendicular from the shore into the marsh. The nets serve as one boundary of our playing field. The water acts as the second boundary, as the sparrows dislike flying over the shoreline. Three of us station ourselves about 30m from the nets, perpendicular to the shore, forming the third boundary, while the fourth guards the area at the end of the last net into the marsh and forms the final boundary (Figure 1).

Three of us line up 30m from the nets and begin marching towards the nets, crazily flourishing long bamboo poles. This is to startle birds up from their hiding spots in the tall reeds. As we progress, birds hop and flit away from us, towards the nets. Some try to escape by flying further into the marsh, but our fourth member acts as goalkeeper, waving his or her pole from side to side to contain the birds (Figure 2).

As we do all of this, it is not unusual that at least one, if not all, of us, gets mired or falls in the spongy, wet marsh. Sinking teammates emit yelps of surprise and then struggle to pull themselves out of the ground, tugging on clumps of vegetation for leverage. We are usually convulsing with laughter at this point, which makes it difficult to extricate ourselves from the waist-deep sinkholes that grudgingly burp us up with loud sucking sounds and great gushes of sulfurous water.

When we get within 10m from the nets, we start sprinting as fast as we can, shouting and waving our poles to startle the birds we are herding. This frightens them to the point that they recklessly burst into flight, right into our nets. Given the physical attributes of our playing field, it’s often like this:

Joe: Ok, let’s press ‘em!

(Joe promptly falls in the mud. Tracy sinks waist deep in the mud and tries to crawl the remaining 7m to the net, still brandishing her pole. Laura is slowly dragging herself out of a mud pit. Only Eileen remains standing and successfully completes the run to the nets.)

We also spend a fair amount of time nest searching—that is, searching for sparrow nests within the grassy marshland. We painstakingly peer into thickets of reeds and gently tease apart tufts of grass, hoping to stumble upon the small woven nest of a seaside sparrow. We’re rewarded from time to time with the discovery of a small nest of eggs or chicks, but more often than not, we get stabbed in the eyes, hands, and legs by the quill-like plants that the sparrows favor for their nests.

Tracy writes:

I wrote this essay because this field experience had been like none I had ever experienced. Fearing the fragility of human memory, I wanted to carefully document the things I saw and did and experienced. This wasn’t the first time I felt compelled to write about a field job, and it certainly won’t be the last. Field biology has given me a truly remarkable life, and I am excited to see where it next takes me.

Tracy Burkhard is a graduate student in the Ecology, Evolution and Behavior program at the University of Texas at Austin. Her current research focuses on the evolution of songs in mice, taking her into the cloud forests of Costa Rica in search of the little brown singing mice (Scotinomys teguina) that make an elaborate trilling vocalization.